David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane (1973) is often seen as a transitional work—psychologically, sonically, and thematically. It followed the breakthrough Ziggy Stardust (1972), but rather than resting in the glam-rock success, Bowie veered toward a fractured, transatlantic take on fame, chaos, and cultural decay. Here's a deep, post-psychedelic analysis of the album’s conception, production, release, reaction, and legacy through a psychedelic lens—focusing on inner fragmentation, cultural feedback loops, and post-acid disillusionment.

Conception: Ziggy's Crash Landing

Bowie wrote Aladdin Sane mostly while on the U.S. leg of the Ziggy Stardust tour, absorbing the dissonant vibes of Nixon-era America: urban decay, decadence, paranoia, and nihilism wrapped in glitz. The title is a pun—“A lad insane”—suggesting a psychological split. If Ziggy was Bowie’s psychedelic prophet of glam transcendence, Aladdin Sane is what happens after the comedown: fragmentation, disillusionment, and overstimulation.

Think of it as the afterburn of the acid age—where the utopian ideals curdle into decadent self-destruction. The album carries that energy: electric, gorgeous, chaotic, and existential.

Production: Dissonant Glam and Schizophrenic Jazz

Produced by Bowie and Ken Scott, the soundscape of Aladdin Sane is both polished and jagged—often within the same track. Pianist Mike Garson's avant-garde jazz breaks (notably on the title track) feel like psychic ruptures. His performance on “Aladdin Sane (1913–1938–197?)” is particularly telling: discordant, unmoored, it references eras on the brink of war or collapse, suggesting history’s cyclical madness.

The psychedelic influence here is post-LSD—less about transcending the self and more about witnessing its disintegration. It’s glam rock with jazz interludes, soul hints, and cabaret horror. The production mirrors a mind overstimulated and splintering, like the neon flashes behind closed eyelids after a long trip.

Release & Immediate Reaction: Glamorously Unsettling

Released in April 1973, Aladdin Sane was a commercial hit (his first #1 UK album), but critics were divided. Many expected a repeat of Ziggy, but what they got was a far darker mirror—Ziggy gone to America and lost in its cultural kaleidoscope.

Songs like “Cracked Actor” and “Panic in Detroit” turned rock-star decadence into something grotesque and haunted. The psychedelic scene—already dying by the early ’70s—would’ve seen this as a natural endpoint. Where the '60s were about spiritual awakening, Bowie painted a world where fame, drugs, and war rendered awakening impossible.

Legacy: Glam's Psychedelic Hangover

Aladdin Sane is now understood as one of Bowie’s most daring records. It captures the moment where psychedelia turns to surrealism, and identity becomes fluid, dangerous, and performative. It’s a glam rock album haunted by jazz and madness—post-acid but still hallucinating.

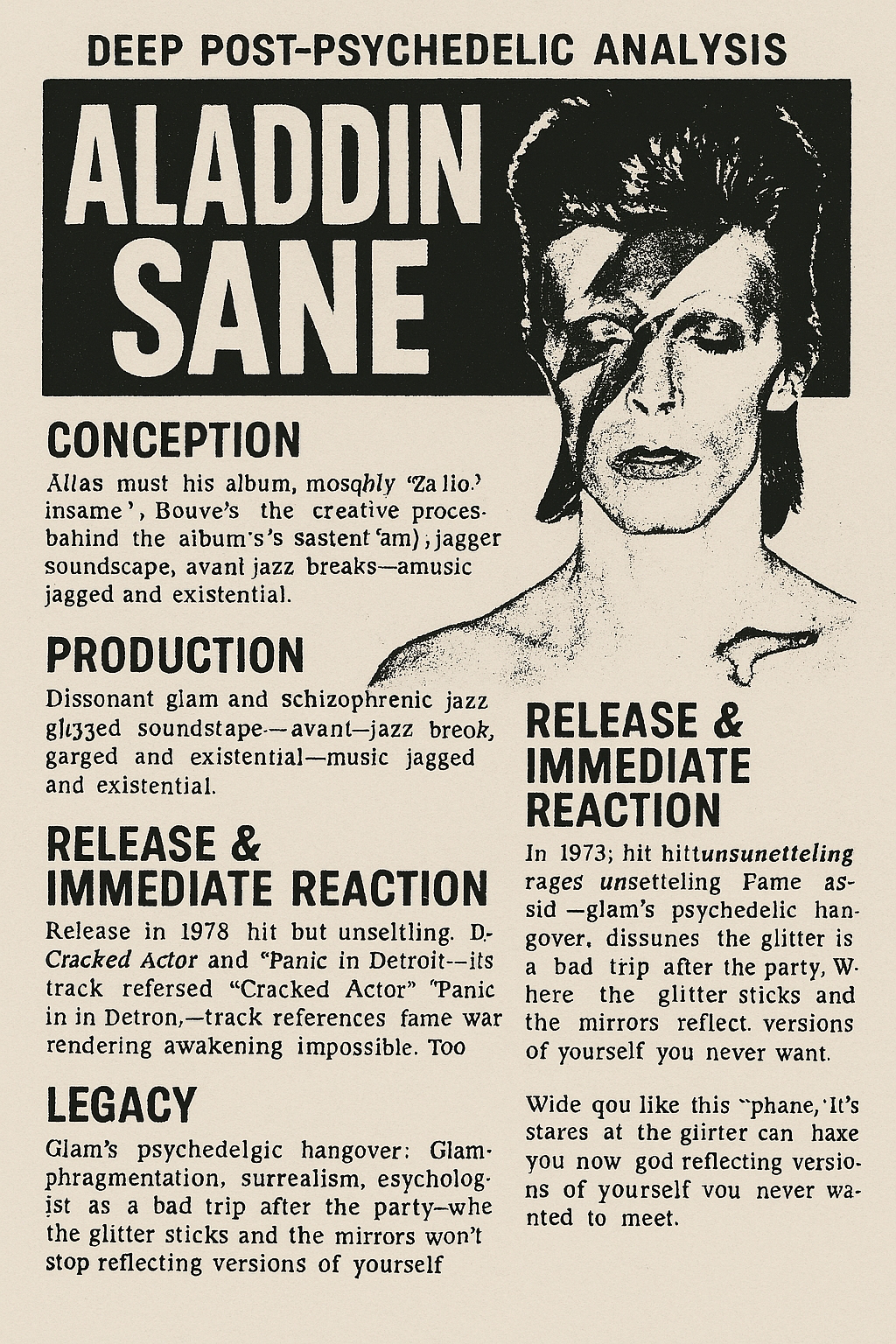

The iconic lightning bolt on Bowie’s face (shot by Brian Duffy) encapsulates this: the self fractured by electricity, fame, and internal conflict. It’s not peace and love anymore—it’s survival through reinvention.

Aladdin Sane doesn’t seek transcendence; it stares at the glittering wreckage of the ’60s and says, “This is your new god.”

If Ziggy was the high, Aladdin Sane is the bad trip after the party—where the glitter sticks to your skin and the mirrors won’t stop reflecting versions of yourself you never wanted to meet.

No comments:

Post a Comment