I. Introduction: John Farrow, the Phantom Craftsman

John Farrow occupies a peculiar space in Hollywood history: a director who never became a household name, but whose films pulse with a formal precision, thematic depth, and a dark lyrical energy that remains undiminished. Born in Australia and steeped in Catholic mysticism, naval discipline, and literary erudition, Farrow brought a controlled chaos to his noirs—films whose surfaces glint with genre convention, but underneath beat hearts of existential anxiety.

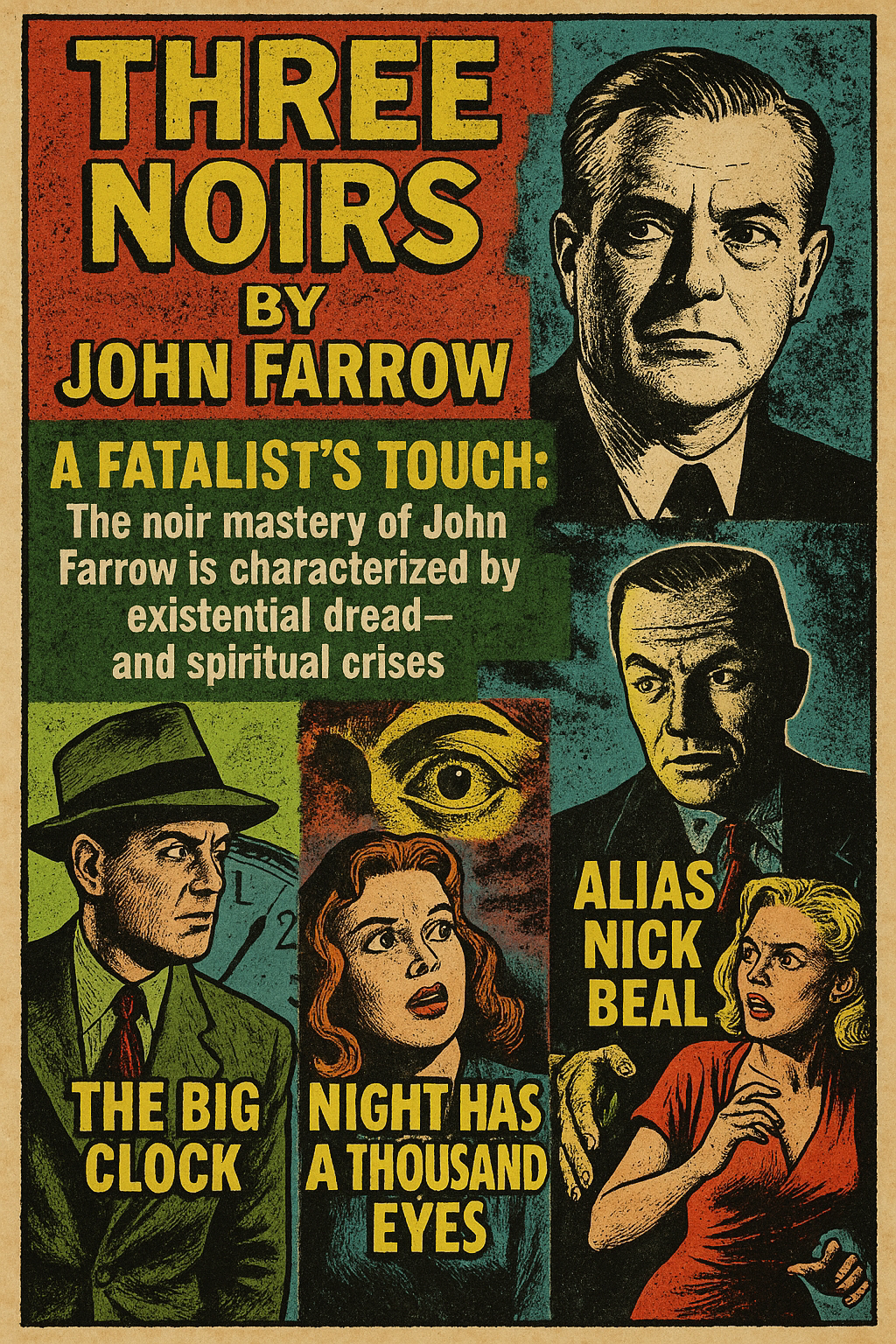

This Criterion Channel trilogy—The Big Clock (1948), Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948), and Alias Nick Beal (1949)—constitutes a crash course in studio-era noir as spiritual crisis. While each film stands alone, together they present a haunting triptych: of time as a trap, fate as a stalker, and evil as an uninvited guest who never quite leaves.

II. The Big Clock (1948)

“I’m being chased by the very system I helped build.”

Themes and Analysis

Adapted from Kenneth Fearing’s novel, The Big Clock is often lumped into the “wrong-man” subgenre. But Farrow elevates it into something closer to Kafka by way of corporate paranoia. Ray Milland plays George Stroud, an editor caught in a manhunt inside his own office tower—a gleaming temple of capitalism that becomes a labyrinthine nightmare. The titular clock isn't just a McGuffin; it's a metaphor for bureaucracy’s inescapable surveillance, and time itself as a predator.

Farrow directs with architectural clarity. The sets are modernist nightmares—clean, brutal, echoing. The camera movements, often steady but claustrophobically tight, make the tower feel like it’s breathing. Every tick of the clock ratchets up existential dread. Charles Laughton plays his role with corpulent menace, a CEO-god watching his creation implode.

Legacy

Think Brazil before Brazil, a postwar bureaucratic hellscape dressed in noir lighting. It’s a workplace thriller that predates The Parallax View, All the President’s Men, or even Severance by decades.

III. Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948)

“I see things… I don’t want to see.”

Themes and Analysis

Adapted from a Cornell Woolrich story, Night Has a Thousand Eyes is Farrow’s most poetic, doom-struck film. Edward G. Robinson plays a psychic—maybe a fraud, maybe cursed—who is haunted by his accurate visions of disaster. It’s noir wrapped in supernatural fatalism, yet directed without a trace of camp.

Farrow leans into ambiguity: is destiny fixed? Are we just watching puppets dance? What makes this film devastating is not the clairvoyance gimmick but the psychic's guilt. Robinson plays him like a man trapped between prophecy and powerlessness.

The cinematography bathes the urban night in ethereal blacks and silvers, creating an atmosphere where streetlamps feel like interrogators. The dreamlike pacing—intercut with sudden shocks—makes this feel more like a precursor to The Twilight Zone or even Mulholland Drive than a typical noir.

Legacy

This is noir as metaphysical inquiry. It deserves to be discussed alongside Detour or Out of the Past, but it digs even deeper—into the question of knowing as its own kind of damnation.

IV. Alias Nick Beal (1949)

“He came out of the rain. No past. No records. Just... appeared.”

Themes and Analysis

Farrow’s take on the Faust myth is his most baroque and experimental. Here, noir crosses into full-blown allegory. Ray Milland plays Nick Beal, a Mephistophelean fixer who offers a righteous D.A. (Thomas Mitchell) a path to political power—at a slow, soul-eroding cost.

This is noir as morality play: an urban parable about compromise, the allure of expedience, and the corrosive price of ambition. Farrow again uses expressionist lighting, smoky interiors, and unsettling angles to make Beal’s presence feel like rot creeping under the wallpaper.

Milland plays the devil not as a monster but as a smooth operator—urbane, whispery, slightly amused. It’s chilling. There are echoes here of Angel Heart, Devil’s Advocate, and even Blue Velvet.

Legacy

A noir that touches on the metaphysical structure of evil—rare for its time, or any. Alias Nick Beal is less a thriller than an urban nightmare about how modernity cloaks damnation in bureaucracy and charm.

V. Farrow's Signature

Across these films, John Farrow's hallmarks emerge:

-

Fatalism with Teeth: All three protagonists are manipulated by systems larger than themselves—be it fate, corporate power, or the devil himself.

-

Architectural Space as Doom: Rooms, offices, alleyways—all become traps. Farrow’s direction emphasizes how structure (physical and moral) constrains human agency.

-

Moral Ambiguity: There are no clean heroes. Every good intention teeters on the edge of compromise.

-

Catholic Underpinning: Farrow’s spiritual background is felt subtly but deeply—through themes of guilt, redemption, and temptation.

VI. Conclusion: Noir as Theology

John Farrow didn’t just direct noirs—he chiseled them like gothic cathedrals out of pulp marble. If other noir directors dealt in shadows and smoke, Farrow dealt in moral weather systems. These three films—The Big Clock, Night Has a Thousand Eyes, and Alias Nick Beal—form a cosmic arc: from mechanized modernism, through cursed clairvoyance, to Faustian fall.

Farrow, long underappreciated, deserves to be mentioned alongside Lang, Tourneur, and Preminger. His noirs weren’t just crime stories. They were ghost stories told by angels who’d fallen too far to go home.

No comments:

Post a Comment