Friday, January 31, 2025

Pay Your Rates

Thursday, January 30, 2025

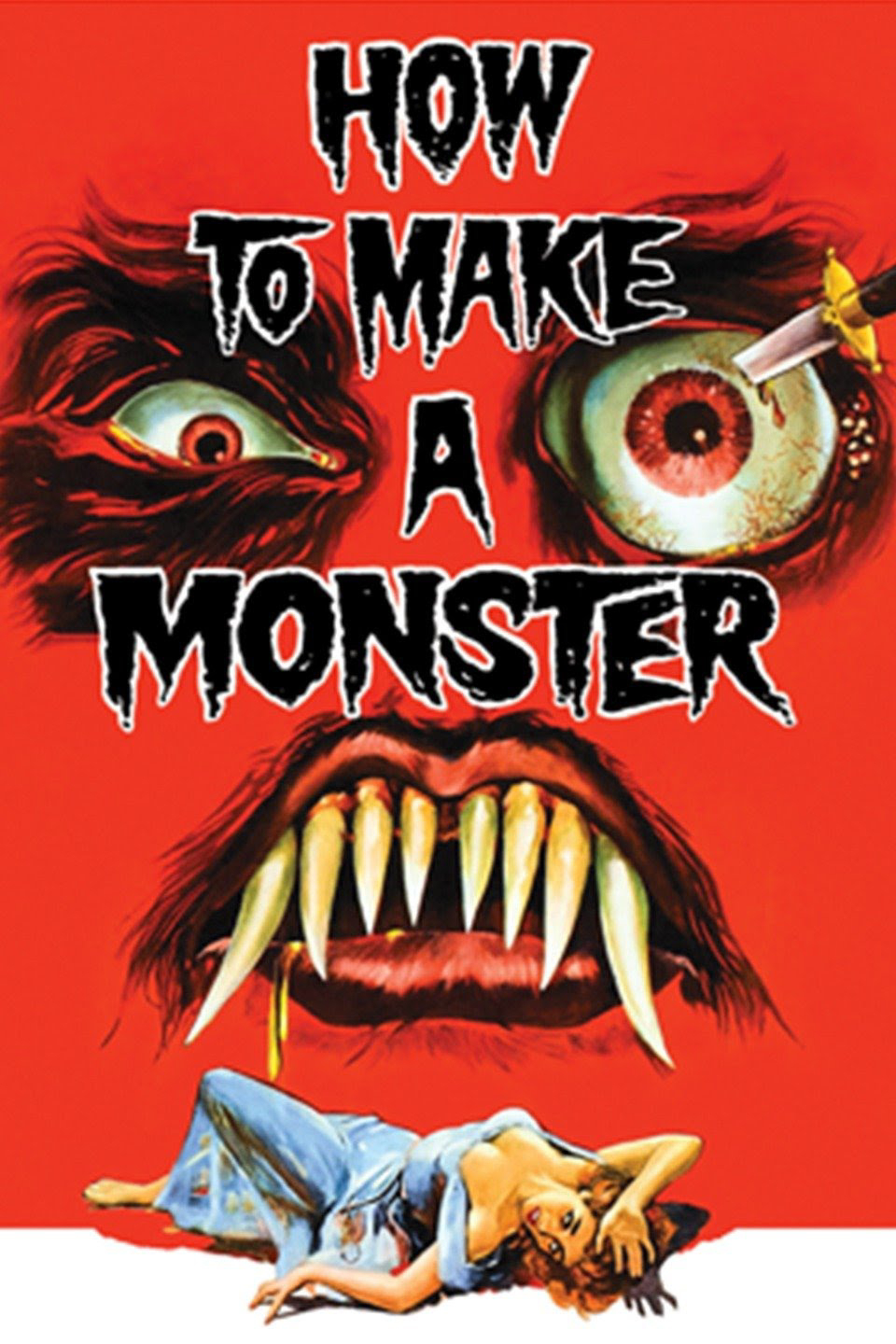

How to Make a Monster (2002) A Proto-AI Horror Story for the Digital Age

How to Make a Monster (1958): The Birth of Special Effects as Rockstars

In the pantheon of 1950s horror films, How to Make a Monster (1958) stands out as a self-referential and oddly prescient entry. At first glance, it is another B-movie from American International Pictures (AIP), known for its low-budget but wildly entertaining horror and sci-fi films. However, beneath its campy exterior lies a fascinating glimpse into the world of special effects and makeup artistry—a world that would explode into mainstream pop culture in the 1980s, elevating effects artists to the level of rockstars.

The Story: Monsters Behind the Scenes

Unlike most horror films of its era, How to Make a Monster is set within the film industry itself. The plot follows Pete Dumond, a special effects makeup artist who, upon learning that his studio is shifting away from monster movies, exacts revenge using mind-control makeup on two young actors. These unsuspecting teens, previously playing the Teenage Frankenstein and Teenage Werewolf (a direct nod to AIP’s earlier films), are turned into real-life murderers under Dumond’s influence.

The film functions as both a horror story and a meta-commentary on the film industry’s treatment of monster movie craftsmen—underscoring their vulnerability as trends change. Dumond, though cast as a villain, is also a tragic figure: a man discarded by a studio eager to embrace the new wave of mainstream Hollywood entertainment. This theme of special effects artists being both revered and cast aside foreshadowed a similar struggle that effects legends would face decades later.

The Makeup Artist as Mad Scientist—A 1980s Parallel

In many ways, Pete Dumond is an exaggerated prototype of the effects gurus who would become household names in the 1980s: Rick Baker, Tom Savini, Rob Bottin, and Stan Winston, to name a few. The 1950s rarely put the spotlight on effects artists, yet How to Make a Monster made the craft—and its practitioners—the centerpiece of the horror story itself.

This shift toward recognizing the effects artist as an integral creative force would not truly come to fruition until the 1980s, when practical effects became a dominant art form. Films like An American Werewolf in London (1981) and The Thing (1982) were not just about their terrifying creatures—they were showcases for the ingenuity of their effects teams. Just as Dumond saw monsters as his masterpieces, these later artists were no longer behind-the-scenes technicians but celebrated figures in horror culture.

A Film That Knew Its Place in History

The film’s final act is particularly poetic. Dumond’s lab, filled with masks and props from previous monster films, is destroyed in a fire—a symbolic farewell to the golden age of 1950s horror. This destruction eerily mirrors what happened to practical effects in the 1990s, as CGI took over as the industry’s preferred tool for creature creation.

Despite its modest budget and campy premise, How to Make a Monster serves as an unlikely love letter to practical effects. Its reverence for the craft foreshadowed a time when the horror genre would fully embrace effects artists as stars in their own right.

The Remake and the Evolution of the Theme

A remake of How to Make a Monster was released in 2001 as part of Cinemax’s Creature Features series, but it took the concept in a different direction, adapting it for a video game-centric era. While it lacked the original's underlying reverence for practical effects, it served as an example of how the "mad effects artist" archetype evolved, now shifting into the realm of digital horror.

Still, the 1958 film remains a fascinating relic—one that, in its own way, anticipated the rise and fall of practical effects as a dominant force in horror filmmaking. Though Pete Dumond was a villain, the film almost seems to argue that the real tragedy was the industry’s abandonment of the artists who made monsters possible in the first place.

Rewatching *The X-Files* in 2025: A Nostalgic and Surreal Experience

Wednesday, January 29, 2025

Listen

Tuesday, January 28, 2025

The Seeds - A Web of Sound: A Lost Proto-Punk Masterpiece

drink up and leave

Might is Right vs. Science Without Restrictions: The Ongoing Legacy of 1950s Sci-Fi and Horror Themes

Tune In Tuesday: Inner Sanctum Mysteries Collection

Outer Order TV?

Bakshi

The Art of Falling Apart: Soft Cell's Unraveling Masterpiece

Monday, January 27, 2025

Wow Za

"Eight Miles High" by Golden Earring—who knew the Dutch could conjure up such a mind-melting spiral of sound? Man, this track is heavy, freaky, and downright cosmic, stretching across the stars like it’s got a rocket ship engine strapped to it. That distorted bass solo? Well, it’s a time-bending moment in rock history, so primal and thick with fuzz, it practically invents the genre of sludgy heaviness that would be perfected by Sabbath a few months later. You’re hearing the rumblings of a beast about to wake up, baby, and it ain’t gentle—it’s ominous, it’s raw, it’s like a serpent on fire.

Let’s talk about that bass. It’s a warping force in itself—climbing, contorting, and then blooming into this gritty, snarling beast that rattles your bones. It’s a bridge between the psych-rock haze of the late '60s and the fist-to-the-face of metal to come. I’m talking about that throbbing, ear-splitting rhythm that mirrors the very chaotic pulse of the universe. Lemmy would’ve tipped his hat to it, man. You know he would’ve, nodding in approval, looking at those fuzzy tones and saying, "Yeah, that’s the way to do it."

And if you wanna talk about future legends—look no further than Cliff Burton. The raw, guttural force of that bass guitar in "Eight Miles High" is practically proto-Metallica, man. You can feel Burton’s spirit in the air, soaking in every reverberation. The track’s bass doesn’t just follow the beat—it leads it, like a beast of the wild taking over the jungle. Burton, the mad genius, probably listened to this and thought, "Yeah, that’s the sound I want in my band."

But let’s not forget the wild energy of the band. It’s gonzo rock and roll, pure and simple. You can practically see the haze of smoke and feel the sweat dripping off the players as they carve their way through the track like a hot knife through butter. The guitars twist in and out, bending time like the minds of a generation hooked on acid and speed. The tempo fluctuates like it’s on a wild ride—no rules, no boundaries, just pure freedom.

Golden Earring's "Eight Miles High" ain’t just a song, it’s a declaration of intent—psychedelic, space-bound, and loud. It’s as if they took the ‘60s and threw it into a blender with the future of metal and came up with a concoction that, even now, stands as a testament to the chaotic brilliance of rock's most rebellious, gonzo elements. And you better believe Lemmy and Cliff Burton would've been right there, in the thick of it, nodding along to the sound of what was to come. This is the essence of rock’n’roll, man, unfiltered.

Jean Genet!

Future/Now: Playlist Reviews

"Another Waltz" by Frank Zappa

Frank’s back at it, crafting something as bizarre as it is beautiful. This unedited master feels like eavesdropping on the electric brainstorm of a mad scientist. You’re not just listening—you’re spelunking into the wild depths of Zappa’s subconscious.

"The Long Medley" by Jimi Hendrix

If Hendrix were alive today, he’d laugh at how we still haven’t caught up to him. This medley has all the furious virtuosity of a guitar sermon. You don’t just listen to it—you let it disassemble your molecules.

"Dark Star" (Live at the Fillmore) by Grateful Dead

Still the apex of cosmic wandering. If acid had a soundtrack, this would be its magnum opus. Garcia and the gang are your spirit guides as the Fillmore becomes a launchpad to the unknown.

"Spoonful" (Live at the Royal Albert Hall) by Cream

Cream flexes their power trio muscles here, delivering blues that hit you like a ton of bricks. Clapton’s solos sound like they were written in the Book of Rock. This one’s a masterclass in loud, sweaty perfection.

"Soul Sacrifice" (Live at Woodstock) by Santana

When Carlos Santana breaks into that solo, time stops. The bongos, the drums, the whole ensemble—it’s not just music, it’s a revolution caught live on tape.

"Rock Is Dead" (Complete Version) by The Doors

Morrison, the poet of doom, takes us down the rabbit hole one last time. This is a sprawling, apocalyptic blues odyssey where the lines between prophecy and hallucination blur. Rock isn’t dead, Jim—it’s just hiding in this playlist.

"Eight Miles High" by Golden Earring

Golden Earring channels that soaring energy but adds a heavier, murkier vibe to it. It’s trippy, it’s loud, and it’s exactly what 2025 needs.

"Tarotplane" by Captain Beefheart

Here comes the good Captain, armed with a harmonica and a primal growl that could scare the blues itself. It’s abstract, it’s raw, and it’s pure Beefheart. This is the sound of the delta turned inside out and flipped upside down.

Verdict? This playlist has some holy grail jams, a soundscape that reminds you rock isn’t just music—it’s the answer to the question you didn’t know you were asking.

Sunday, January 26, 2025

Peter Hammill: The Lost Prophet of Proto-Punk

There’s a ghost haunting the edges of rock ‘n’ roll, a shadowed figure whose name flickers in the back alleys of conversation but rarely takes center stage: Peter Hammill. And the world’s a worse place for it, because Peter Hammill is the lost prophet of proto-punk, the misunderstood visionary whose flame flickered bright before the world was ready to set fire to it. He was one of the few who understood that rock music could be both a political force and an existential meltdown, a howling cry against the absurdity of life, all while wearing an experimental, cerebral face. Let’s be clear about one thing: Peter Hammill is proto-punk, not in the "I-can-see-the-skinny-jeans-wearing-punks-lurking-around-his-records" way, but in the “I-was-there-before-the-whole-scene-had-a-name” way. And it’s high time we gave him the credit he’s owed.

First, we’ve got to take a step back and ask: what the hell is proto-punk anyway? Is it some kind of accident, a reaction to the corporate monster of the music business, or a psychological spasm of disillusionment that birthed the unholy offspring of Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, and the Stooges? Yes. But there’s more. It’s the moment before everything fell apart, the blurry snapshot of the world in the early 70s, when rock ‘n’ roll had eaten itself and was begging for something with the heart of a rebel but the brain of a philosopher. Hammill’s vision was punk rock before it was punk rock, smoldering under the surface of bands like the Velvet Underground, the early Stooges, and, yes, even the most deviant strains of the British art-rock movement.

Peter Hammill, frontman of Van der Graaf Generator, wasn’t playing by any of the rules. He wasn’t interested in the simple three-chord sneer of the early punks—he was too busy cracking open the skull of rock music and daring you to peek inside. His music swelled with a kind of operatic grandiosity, drowning you in drama, then pulling back into delicate, tender introspection in the same breath. Hammill’s voice, one minute a croon, the next a primal scream, was a precursor to the guttural, anguished delivery that would later become synonymous with punk. The catharsis wasn’t just in the music—it was in the emotional rawness that he wore like a badge of honor.

But let’s not be coy about it—this wasn’t just artistic exploration. There was a visceral anger in his work, a seething fury at the establishment and the self-destructive tendencies of humanity, that smacks of what was to come in punk. “In the End” from The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other is a prime example. Here is a track where Hammill essentially predicts the bleak nihilism that would become punk's bread and butter. His songwriting is visceral, drenched in despair, but there’s a lyrical complexity that sets him apart from those who’d pick up guitars and just scream. He wasn’t merely angry; he was anguished, questioning everything from identity to the very nature of existence.

The tension between intellect and aggression in his work is what sets Hammill apart from the likes of Iggy Pop or Johnny Rotten. Sure, the raw energy of punk was, in many ways, a collective "fuck you" to the rules of rock 'n' roll, but Hammill’s message was more personal, more cosmically ambitious. He was a man with a soul full of ache, screaming about the meaning of life and death, veering dangerously close to the edge of a nervous breakdown. And yet, amidst all that intellectual terror, there’s a rock 'n' roll purity that runs through it. At its core, Hammill’s music is deeply punk in the way it rejects the comfortable, the easy, and the pretty, all while dancing through different musical genres, each more jarring than the last.

His lyrics are biting, cynical, and esoteric, playing with language in ways that most punk bands would never dare. He didn’t just want to play with the formula of pop music—he wanted to dismantle it. On Pawn Hearts (1971), a record that oscillates between brooding experimentalism and jagged riffs, Hammill reaches out into the unknown, trying to grab the world by its throat. The result is pure, unfiltered, unvarnished punk, even if it was happening on a prog rock stage. To see Hammill’s work as anything less than proto-punk is to ignore the seething rebellion simmering beneath the surface.

And then there’s the attitude. It’s tempting to label punk as the domain of the anti-hero, the outcast, the loudmouth who would spit in your face for looking at them wrong. Hammill, though, was more of the tortured artist type—the kind of punk who didn't need to get in your face because his entire existence was a confrontation. The character he projected in his performances was a man grappling with his own fragility, his own profound alienation from the world. He wasn’t trying to be a “cool” rebel. He was a man trapped inside his own disintegrating mind, and that mental collapse was precisely what made him an artist.

The post-punk world, which blossomed in the wake of the 70s explosion, would come to fully embrace this punk-as-psychic-tragedy idea. Think of Joy Division, think of Magazine, think of Wire. But Hammill was already there, standing on the edge of that precipice, howling into the void. His early work was as punk as anything that came after it, even if it didn’t always sound that way at first. There’s a distinct feeling in songs like Killer that insists “I’m here, I’m pissed off, and I’m not going to make it easy for you.” And isn’t that the essence of punk? Not the glib cynicism, not the fashion, but the primal need to destroy everything and then build something real from the wreckage?

Peter Hammill never sought fame. In fact, he actively avoided it, preferring to stay in the shadows, where his work could remain jagged, confrontational, and misunderstood. And that’s fine by me. But it’s time we acknowledge the debt punk owes him. Punk isn’t just about sneering through leather jackets and spitting on the floor—it's about anguish, emotional wreckage, and a refusal to let society win. Peter Hammill understood this better than anyone, and for that reason, he deserves to be crowned as the lost prophet of proto-punk, a godfather to the revolution that no one gives him credit for contributing too.

Thursday, January 23, 2025

Spawn (1997)

Spawn (1997): A Time Capsule of Mid-to-Late '90s Culture

Spawn, the 1997 film adaptation of Todd McFarlane's edgy comic series, is a masterpiece—not in a conventional sense of flawless cinema but as a cultural artifact. It perfectly encapsulates the mid-to-late 1990s with a chaotic charm that no other film could replicate. Whether through its groundbreaking (yet flawed) CGI, industrial-metal soundtrack, or angsty antihero narrative, Spawn feels like the ultimate representation of the era.

Aesthetic Chaos

The late '90s was a time of rapid technological experimentation, and Spawn dives headfirst into this trend. The CGI—while dated by today’s standards—was revolutionary for its time, attempting to push boundaries in ways that mirror the burgeoning fascination with digital innovation in the decade. The hellscapes are garish, over-the-top, and unapologetically loud, echoing the era's tendency to go big or go home in visual effects.

The film's grunge-inspired aesthetic, featuring leather, chains, and heavy shadows, embodies the darker, more rebellious side of late-'90s pop culture. Spawn himself is an emblem of the antihero trend—flawed, brooding, and vengeful—a perfect match for the cultural fascination with edgy, morally ambiguous protagonists.

Soundtrack of the Times

The soundtrack is perhaps the film's most potent timestamp. A fusion of industrial and electronic music, it features collaborations between artists like Marilyn Manson and The Prodigy, Slayer and Atari Teenage Riot, and Metallica and DJ Spooky. This blend of metal and electronica speaks directly to the musical experimentation of the late '90s, where genres collided to create something chaotic and new.

The Angst of an Era

The late '90s was a time when anti-establishment sentiment and existential angst permeated pop culture. Spawn captures this perfectly through its story of betrayal, vengeance, and redemption. Al Simmons, a betrayed soldier turned hellish antihero, mirrors the disillusionment with institutions and authority figures that was prevalent during the era.

The film also reflects the decade’s obsession with dark, "mature" storytelling, epitomized by comic book adaptations like The Crow and TV series like The X-Files. Spawn fits right in, offering a narrative that’s more gritty than polished, more visceral than thoughtful.

Flaws as a Feature

Critics have often dismissed Spawn for its uneven tone, inconsistent writing, and visual excess. But those very flaws make it a perfect artifact of the '90s, a decade that was itself chaotic and experimental. Like the dot-com boom or the rise of nu-metal, Spawn is a product of its time, and its imperfections only enhance its nostalgic appeal.

Conclusion

To watch Spawn is to step back into the cultural zeitgeist of the late '90s—a time of boundless ambition, reckless experimentation, and a love for all things dark and edgy. It’s a film that screams, “This is the ‘90s!” louder than almost any other. While it may not be a cinematic masterpiece in the traditional sense, it stands as a perfect representation of an era defined by its bold, messy, and wonderfully weird spirit. For that reason, Spawn deserves its place as a cultural time capsule and, arguably, the greatest representation of the mid-to-late '90s you will find.