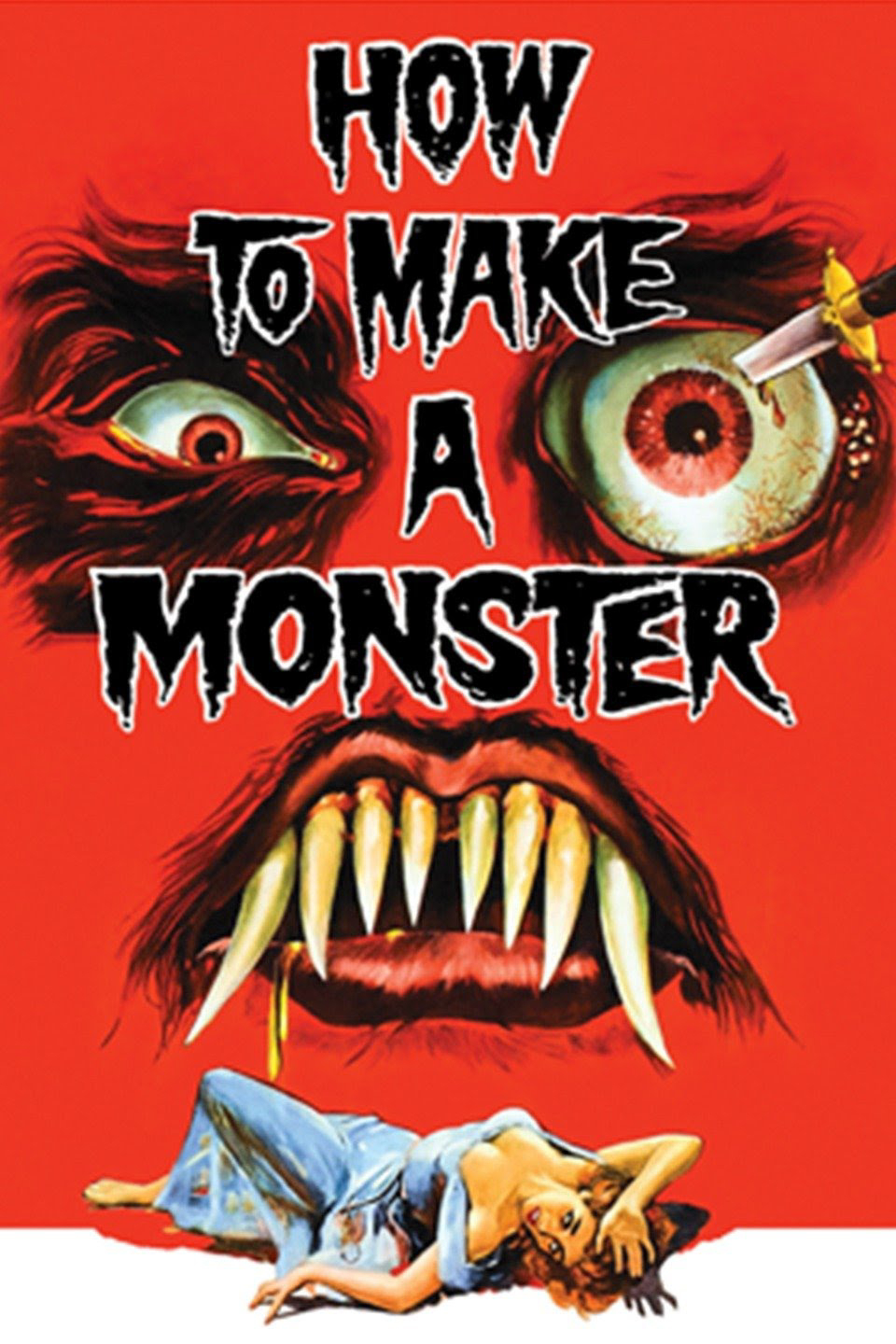

In the pantheon of 1950s horror films, How to Make a Monster (1958) stands out as a self-referential and oddly prescient entry. At first glance, it is another B-movie from American International Pictures (AIP), known for its low-budget but wildly entertaining horror and sci-fi films. However, beneath its campy exterior lies a fascinating glimpse into the world of special effects and makeup artistry—a world that would explode into mainstream pop culture in the 1980s, elevating effects artists to the level of rockstars.

The Story: Monsters Behind the Scenes

Unlike most horror films of its era, How to Make a Monster is set within the film industry itself. The plot follows Pete Dumond, a special effects makeup artist who, upon learning that his studio is shifting away from monster movies, exacts revenge using mind-control makeup on two young actors. These unsuspecting teens, previously playing the Teenage Frankenstein and Teenage Werewolf (a direct nod to AIP’s earlier films), are turned into real-life murderers under Dumond’s influence.

The film functions as both a horror story and a meta-commentary on the film industry’s treatment of monster movie craftsmen—underscoring their vulnerability as trends change. Dumond, though cast as a villain, is also a tragic figure: a man discarded by a studio eager to embrace the new wave of mainstream Hollywood entertainment. This theme of special effects artists being both revered and cast aside foreshadowed a similar struggle that effects legends would face decades later.

The Makeup Artist as Mad Scientist—A 1980s Parallel

In many ways, Pete Dumond is an exaggerated prototype of the effects gurus who would become household names in the 1980s: Rick Baker, Tom Savini, Rob Bottin, and Stan Winston, to name a few. The 1950s rarely put the spotlight on effects artists, yet How to Make a Monster made the craft—and its practitioners—the centerpiece of the horror story itself.

This shift toward recognizing the effects artist as an integral creative force would not truly come to fruition until the 1980s, when practical effects became a dominant art form. Films like An American Werewolf in London (1981) and The Thing (1982) were not just about their terrifying creatures—they were showcases for the ingenuity of their effects teams. Just as Dumond saw monsters as his masterpieces, these later artists were no longer behind-the-scenes technicians but celebrated figures in horror culture.

A Film That Knew Its Place in History

The film’s final act is particularly poetic. Dumond’s lab, filled with masks and props from previous monster films, is destroyed in a fire—a symbolic farewell to the golden age of 1950s horror. This destruction eerily mirrors what happened to practical effects in the 1990s, as CGI took over as the industry’s preferred tool for creature creation.

Despite its modest budget and campy premise, How to Make a Monster serves as an unlikely love letter to practical effects. Its reverence for the craft foreshadowed a time when the horror genre would fully embrace effects artists as stars in their own right.

The Remake and the Evolution of the Theme

A remake of How to Make a Monster was released in 2001 as part of Cinemax’s Creature Features series, but it took the concept in a different direction, adapting it for a video game-centric era. While it lacked the original's underlying reverence for practical effects, it served as an example of how the "mad effects artist" archetype evolved, now shifting into the realm of digital horror.

Still, the 1958 film remains a fascinating relic—one that, in its own way, anticipated the rise and fall of practical effects as a dominant force in horror filmmaking. Though Pete Dumond was a villain, the film almost seems to argue that the real tragedy was the industry’s abandonment of the artists who made monsters possible in the first place.

No comments:

Post a Comment